Looking for Secrets, Listening to Silences: One Immigrant’s Uncharted Life

By Marta Cieślak

Author’s note: I have come across Marianna’s story while doing research on Polish women immigrants in the United States. I am not related to Marianna, and I do not know anyone who may be. To protect her privacy and the privacy of her family, I have changed names and limited identifying information. This is also why I do not cite my sources although all life events discussed below are documented. Marianna’s story is only one immigrant’s uncharted life. Find out how you can share your story.

This post contains material about domestic violence.

Wife, Mother, Worker

Marianna was born in a village in Austrian Poland in 1888. She migrated to the United States in 1906. Shortly after that, at the age of 18, she married Fryderyk, who came from the same village in Galicia. The two settled in Massachusetts, where Fryderyk, whom everyone now called Fred, had joined his brother Mateusz a year before Marianna’s arrival.

We do not know much about Marianna, but we can piece together a patchy story of her life. She knew how to read and write so she must have received at least rudimentary education. It is not clear whether she migrated to the United States specifically as Fred’s bride but the timing of their marriage and the fact that they both came from the same village suggest it is a possibility. Young single immigrant men often came to the United States alone, settled down, and started looking for a wife, usually in or from their homeland. Polish migrants who crossed the Atlantic before 1914 did not simply want to marry other Polish migrants. They preferred to marry someone from their home village, town, or at least the general area that they left behind.

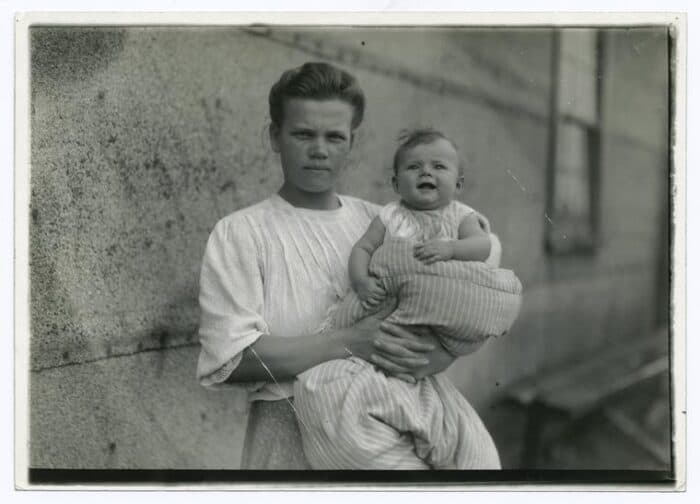

Already in 1907, only a year after marrying Fred, Marianna had her first child. When Kathleen was born, the young family was renting a house. Marianna had her hands full as the family shared their home with seven other individuals. Some of them were relatives, including Fred’s two brothers, Mateusz and Andrzej, and Mateusz’s wife. Two young single women and a married man – all from Austrian Poland – lived with the family as boarders. Keeping boarders was a relatively common practice among contemporary immigrants, not only Poles. It was a way to make extra money for the host family and an affordable and practical living arrangement for those who migrated alone. The seventh additional household member was Fred’s two-year-old nephew, who at one point mysteriously lived with Marianna and Fred but without his parents.

All adults in the household except Marianna worked at a local cotton mill. So although Marianna was not the only woman in the household, she was the primary caregiver. While single working class migrant women almost always worked outside of home and married working class women oftentimes worked for wages until they started having children, a baby in a married woman’s life usually meant leaving the waged labor market. Marianna’s story confirms this pattern although we do not know whether she worked outside of home before having Kathleen. What we know is that she did not have a waged job after her first child was born. While her sister-in-law and two female borders went to work at the cotton mill every day, Marianna stayed at home, most likely taking care of Kathleen and all the others.

Incomplete records suggest that Marianna had at least seven more children, but it is possible that the number was higher. That also makes her a rather typical working class immigrant of the era. Polish, Italian, and Jewish families were at the time the largest among the populations the US bureaucratic state categorized as white. On average, Polish women of the pre-1914 migration wave had more children than their American-born peers.

Secrets and Silences

All these details fit in a collective portrait of Polish women migrating to the United States prior to the outbreak of World War I established by historians. Marianna was of rural descent (a peasant, as they say…). Nearly overnight she transitioned into the industrial working class. She married young, gave birth to many children, and spent her days in an industrial town taking care of her family and boarders. Her reading and writing skills were less typical among particularly female migrants of the era but she certainly was not the only woman migrant who had some education.

But many silences in Marianna’s life paint a much more complex picture. Something happened in 1910. That year Kathleen, at the time barely three years old, traveled to her parents’ home village in Galicia to stay there until 1922. A three-year-old obviously could not have travelled alone but we do not know if Marianna went with her. Even if she did, Kathleen stayed with her parents’ relatives for twelve years. Marianna, if she had travelled with her daughter at all, must have returned to the United States by spring 1913. We know that because in 1913 Fred beat Marianna up in their American home. He was already drunk when he asked Marianna to give him 10 cents for beer. She refused. After angry negotiations, Marianna agreed to give him 5 cents. Fred responded with violence. The outburst landed him in jail for 30 days.

Only a year after this incident, Marianna gave birth to another daughter, Amelia. This suggests that sending Kathleen away did not mean Marianna was done with motherhood. Neither did the potential trip to the home village signal that Marianna planned to escape her marriage, at least not long-term. Following Amelia, Marianna and Fred had at least five more children. They remained married until Fred’s death in the 1930s.

In 1940, Marianna was a widow and six of her children lived with her. Her life was now less like a typical life of a rural woman who arrived from Eastern Europe and more like that of a white working class woman in the industrial United States of the almost-mid-20th century. No longer was Marianna taking care of extended family or boarders. Her three youngest were at school, as most American urban children at the time. Her three oldest worked and were able to support the family of seven, a notable accomplishment given that it was still the Great Depression. Marianna’s oldest son was a high school graduate. One of the daughters even made better wages than her older brother, despite having less education.

Questions and Fragments

This very incomplete story reveals some common challenges of mapping the uncharted lives of immigrant women from the pre-1914 migration wave. We know that shortly after arrival in the United States, Marianna became a hard-working wife and mother. Her caretaker shift must have been backbreaking given the extended family, the boarders, and the increasing number of children. This surprises hardly anyone familiar with the stories of ordinary immigrant women in the early 20th century. But what happened in 1910? Who decided that barely three-year-old Kathleen should live in Marianna’s ancestral land? Why didn’t Marianna stay with Kathleen in Galicia if she went at all? Why did Kathleen stay in her mother’s village until 1922, when at the age of 15 she applied for a passport? Evidence suggests that Kathleen returned to the United States. She did not reconnect with her mother. Was she angry with Marianna? Did she resent her mother for growing up without Marianna and away from the first home she knew?

Other questions emerge too. Was the 1913 outburst of domestic violence an exception or a more common occurrence? Was it a shocking incident that compelled Marianna to involve the police? Or was it a recurrent experience and that time Marianna lost her patience? Or, if the violence documented in 1913 was not an isolated episode, did she report Fred’s actions regularly, but we simply have no record of her struggles?

Finally, what do we make out of the complexities of patriarchy in Marianna’s story? On the one hand, Marianna was an overworked mother and wife that was forced to deal with a drunk violent husband. On the other, she negotiated a level of independence and agency within that violent patriarchal world. First, she was in control of the home budget. After all, Fred got angry because she refused to give him 10 cents for more beer as, presumably, he did not have access to that money without her permission. Second, she alerted the authorities when her husband hit her, which made the act of violence that had occurred in the privacy of Marianna’s home public knowledge. Some eyewitnesses found it amusing that, as they claimed, it was five cents that landed Fred in jail (remember that Marianna eventually agreed to giving Fred five cents). Of course, it was not five cents. It was violence and Marianna’s courage to report it.

One Immigrant’s Uncharted Life

Marianna’s story reveals multiple negotiations, through which working class immigrant women established their place and roles in the society. And let’s not forget that Polish women, just like women in any immigrant community, carried a double weight of social expectations. There was the Polish or Polish American community and there was the mainstream American society. Each created their own image of what immigrant women should be but stories like Marianna’s remind us that the women negotiated their place between what was expected of them and their resistance to those expectations. Marianna was a young bride, busy mother, and industrious landlady, or everything the society presumed she could and should be. But she was neither the silent Virgin Mary-like caretaker that many of her fellow Poles wanted her to be nor the helpless, backward, and ignorant immigrant that her fellow Americans imagined her to be. Her motherhood experience contained a mystery of a child left behind in the distant homeland. Her marriage was a negotiation between violence directed at her and control that she exercised over her husband. And part of that control must have come from the housework that she did every day and that was indispensable to the survival of the family but that the society considered hardly work at all.

The world around Polish immigrant women in the late 19th and early 20th centuries expected a lot of them, as it expected a lot of all working class immigrant women, or perhaps all women but especially those who did not enjoy many privileges. The women dutifully met some of those expectations but they also resisted others. Some immigrants resisted fiercely and openly. Others were more subtle and their resistance more invisible to the eye of an outsider. While we may never fully know their stories, just like we know only some pieces of Marianna’s story, it is worth asking what their stories might have been and at least try to find some answers, if only fragmentary. Because even fragmentary, incomplete stories make it clear that Polish immigrant women in the United States were conflicted about their identities and place in the world around them. As much as they served the roles of devoted mothers and wives, they also made their secret and not-so-secret decisions that perhaps never fully undermined patriarchy but that never fully accepted patriarchy either.