Life Hidden In A Composition Book

By Anna Müller

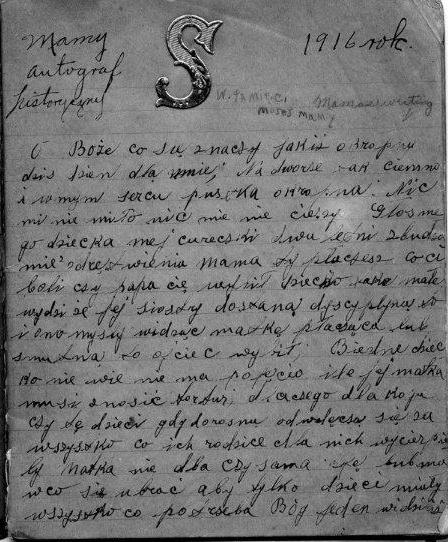

O Boże co to znaczy jakiś okropny dziś dzień dla mnie; Na dworze tak ciemno i w mym sercu pustka okropna. Nic mi nie miło nic mnie nie cieszy. Głos mego dziecka mej cureczki dwu letni zbudził mnie z odrętwienia Mama Ty płaczesz co ci boli czy papa cię …[illegible].

Oh my god what does it mean for me to have such a terrible day today; It is so dark outside and in my heart terrible emptiness. Nothing is good nothing gives me joy. A voice of my child my daughter two years old awoke me from numbness Mama, You’re crying what hurts you did dad…???

All translations from Polish in this post mirror the original spelling and punctuation.

Mysteries of a Composition Book

This is what Edward Martin read on the first page of a composition book he came across in an antique store on Michigan Avenue in Detroit, a place he often visited. It was the early 1990s. Martin regularly checked stores with Polish memorabilia, most of which are no longer there, in one of the Polish American communities in Metro Detroit. Back then, Martin was a medical doctor who devoted his professional life to Michigan. His childhood and youth years were connected to Hamtramck and Orchard Lake, where he attended school at the Polish mission. Looking for and collecting Polish memorabilia have always been his great passion. In the early 1990s, he found two composition books. One was written in 1916 by a woman we know as Wasilewska. The other, from 1935, was written by Irena Wasilewska, most likely Wasilewska’s daughter, perhaps the two-year-old child mentioned in the first sentences of her notes that open this story.

Discoveries like these two composition books are rare, perhaps very rare. The two artifacts reveal very different approaches to keeping personal records. The document from 1916 is a diary, or a type of a journal, in which Wasilewska reflected on her current life. In a desperate voice she also looked back at her entire life: the life she lost and the life she tried to build in the United States. The document ends abruptly, mid-sentence, at the precise moment when the woman’s troubles appear to begin. It never fully explains her situation. Only the first page – as the quote opening this story suggests – implies some reasons that may have pushed her to writing. She finds some consolation in a good life she had prior to her arrival in the US; but in that context, she also questions and regrets ever leaving her home.

The second composition book – the one that belonged to Irena Wasilewska – is different. It is a collection of prayers and songs, in both Polish and English. It begins with a statement that the recorded songs, prayers, and mottos are something that each Polish child should know. Some of them refer to the 19th century, to the struggles between Prussia and Russia over Poland. Some speak about the Bolsheviks and their urge to take over Poland. Somewhere halfway through the document, there is a statement about the importance of the Polish language for Polish children scattered all over the world.

Composition Book as a Source of Life Story

Wasilewska’s journal is short, barely ten pages covered with a hardly legible script in Polish. The text is missing most punctuation marks, making the process of reading cumbersome. Sentences run into each other, further obscuring the text. When the narration reaches moments particularly difficult for the author, Wasilewska begins writing directly to the person she recollects, her father, her sister, a woman who mistreated her, her husband. At times, the author also speaks directly to the reader, demonstrating awareness that one day someone may read her intimate thoughts:

Zapytacie się drodzy czytelnicy, czy też siostrze mej przykro było, nie[?] całe miasto obrażone było jak to jedna siostra drugiej uczynić może mając męża i dzieci nie żał było tych biednych dziadek

You will ask, dear readers, if my sister was not sorry that not[?] the entire city was offended that one sister having a husband and children can do such a thing to the other sister was she not sorry for these poor children

The story the journal conveys is framed as a reflection on an unfortunate life, life as a trap that fate tends to set up. Wasilewska left a happy home to get stuck in an unhappy reality, one that she cannot abandon due to a sense of responsibility for the future of her children and a need to maintain a stable environment for them.

Niestety kogoś los sobie upatrzy i tego zacznie prześladować bez przerwy; tak i ze mną jest od czasu kiedy porzuciłam dom rodzicielski przyjeżdzając do ameryki, she wrote.

Unfortunately, once fate chooses someone, it will haunt them constantly; that’s what’s happened to me since I left my family home and came to america [sic].

From Poland to the United States

Wasilewska arrived in America following in the steps of her sister, probably in the early 1910s. In Poland, she grew up in a city, most likely in the Russian partition of Poland. We can deduce that from the words of her father, who tried to discourage her from leaving and told her to go either to Warsaw or “abroad” but closer to home (Warsaw was in the Russian partition). Her mother died at the age of 32, leaving eight children behind. The author was the youngest. Wasilewska must have been raised in a relatively well-off household. The household had a maid and her father ultimately decided to fulfill his youngest daughter’s dream and paid for her American trip.

The father remarried and, despite Wasilewska’s mother’s death, she remembers her home as full of love. She was loved and loved her father and stepmother. Regardless of this life of content in Poland, her biggest dream was to visit her sister in America. Her father reluctantly agreed to pay for the voyage. She had some money, so for the first months she did not have to work. When the money began to run out, her father wrote to her encouraging her to return. He even suggested that he would pay for her return trip. However, her sister told her not to ask their father for more money and instead find someone to marry. What happened next is unclear. Wasilewska found a job in a bakery, which shows that she may have decided to follow her sister’s suggestion and not to return to Poland. What is certain is that the relationship with the sister deteriorated. A man who was romantically interested in Wasilewska had an affair with her sister when the latter temporarily abandoned her husband and children, perhaps to make Wasilewska jealous. Eventually the sister returned to her family and Wasilewska met Jan, a fellow Pole whom she married. They tied the knot three weeks after meeting for the first time.

The marriage seemed initially happy, but later various problems began to emerge. First, Janina, a relative from Poland, arrived. She stayed with Wasilewska and her husband and appeared to be romantically interested in Jan. Once Wasilewska realized the potential female competition under her own roof, she characterized the relative as German. It is possible that the relative came from German Poland, as it was common for Polish immigrants to make this sort of categorizations. Yet, Wasilewska’s choice to refer to her as German and to herself and her husband as Poles reflect her understanding of the situation:

Janie i ty pozwolisz tej niemce nam polakow ubliżać, mogła by się wstydzić myślałam że zostałaś uczciwą dziewczyną, co ameryka z ciebie zrobiła zazdrość przez cię przemawia

Jan and you let this german disparage us poles, she should be ashamed I thought you became an honest girl, what has America done to you jealousy speaks through you

After problems with Janina lessened, a new challenge emerged. Wasilewska’s husband appeared to have lost his job. She tried to help and be supportive:

Janie, czy sądzisz, że jestem niedoświadczoną nie znam biedy to ja pozwolę tobie a byś poszedł w świat cierpieć nigdy przysięgę złożyliśmy wspólną i dzielić będziemy dolę i niedolę miałam w Bogu nadzieję i mówiłam w męża słuchaj drogi Niech nas cały świat od sobie odepchnie lecz Bóg nas nie opuści …

Jan, do you think that I am inexperienced I do not know poverty that I’ll let you go into the world to suffer never we are married we took an oath together and we will share our fate and misery. I had hope in God and told my husband listen dear Let the world push us away but God will not abandon us …

But here the story ends almost mid-sentence. As readers, we are left wondering what caused Wasilewska’s desperation. Is it the lost home and its happiness? Or did her husband perhaps engage in violence, as the opening sentences of the journal cited above suggest?

Power and Powerlessness

What does Wasilewska’s story reveal? It appears to be unique and quite common at the same time. She certainly knew how to read and write, and if the second composition book did, indeed, belong to her daughter, we may assume she passed on the knowledge of the Polish language to her child. Like many other Polish immigrants, she married another Polish immigrant, remained close to the local Polish community, and experienced marriage struggles.

Wasilewska was unhappy. She regretted leaving Poland. We do not know if she ever returned, or if her children ever visited Poland. We should keep in mind that her life was defined by several decisions she made: her decision to leave Poland, to stay in the US, to choose a man to marry. Even the way she defined herself as a Pole while seeing the people who contributed to her misfortune as Germans speaks to her agency. Her ethnicity – her Polishness, as John Bukowczyk in his book And My Children Did Not Know Me argues – was a matter not only of culture but also of power and powerlessness.